For the inclusion of the Diaspora in Haiti's political process: Leveraging remittances as a powerful resource that can spur positive sociopolitical changes and sustainable development.

A Case Analysis

Written by: HAMREC 02/19/2022

A well-known proverb with disputed origin reads as follows: "Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day. Teach him to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime." In Haiti, there is a stranglehold on the country's most valuable resources by those in power and the upper class, and to a lesser extent, foreign interests. Remittances representing 30% of the GDP are constantly under assault in the name of taxation. Those in power always find mechanisms and new tools to skim a percentage. Unfortunately, this "diaspora tax," as many Haitians call it, always ends up benefitting a few instead of providing services to the population. Haitians living abroad have little say in the affairs of the country. In other words, it is taxation without representation.

The stakeholders are from all walks of life: Migrant senders, politicians, policymakers, regulators, remittance agents, delivery services, banks, regional entities, local villages, remittance recipients, small and large businesses.

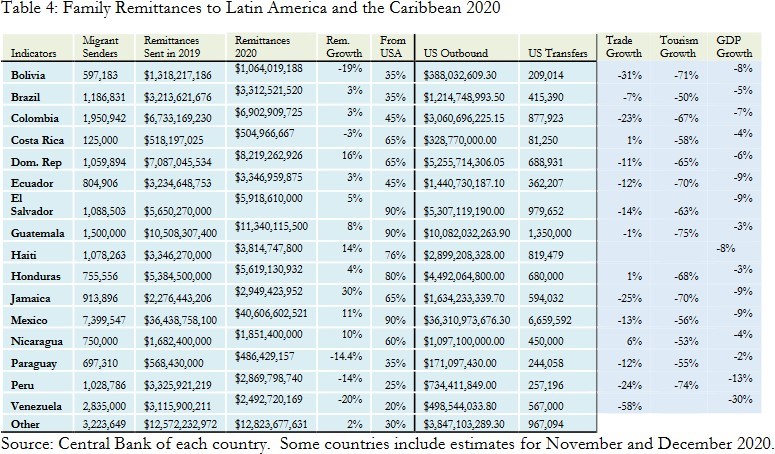

A simple google search shows that expatriates have sent approximately $2 billion yearly to Haiti for over 40 years. In 2020 Remittances reached an unprecedented level of $3.8 billion.

Money transfers exceed tourism and goods exported in terms of GDP. With so much money flowing into the country, it tempted successive government administrations to levy a tax on transfers. Former Haitian president Michel Martelly instituted a $1.50 tax on remittances without transparency. Besides the sending fee, the sender must cope with Haiti's exchange rate margin and levies. Last year, the Haitian central bank decreed those transfers would be paid in local currency unless the recipients had a dollar-only account. It further erodes the autonomy of the money receivers.

Past fights or movements have not been successful at resolving the issue. There had been online petitions that requested a report on the use of the fee. https://chng.it/kdwcVhJDSp. It collected a contemptible nine signatures as of the last count. Another petition posted on change.org against the flat tax of $200 on the Haitian Diaspora https://chng.it/Djd9Q6wxDq collected only 6599 signatures to date. The low numbers may be related to apathy, or an outreach strategy not being done on a larger scale.

The data on diaspora and remittances is a treasure trove for those who wish to research and write. Many journal articles, websites, and books aptly debate various aspects of the same topic of remittances. Many organizations purport to be of the Civil Society, and while many of them do not actively operate in a meaningful sense in Haiti, some may hold even more valuable data.

The short definition of remittances is money that migrant workers send back home. This paper analyzes the value of remittances for the Haitian economy and how the diaspora can use it to make its voices heard in the democratic process. It attempts at answering the following questions:

Problem:• What long-term strategy would allow the diaspora to wield its muscle more effectively to tip the scale of the political landscape in favor of better governance?

• What would be the consequences of a short-period disruption in money flow from the diaspora to their loved ones in Haiti? Can a pause in remittances be significant enough to force the hands of those at the helm? Could such "sacrifice" result in negative economic and political consequences for the regimes, or could it end in resentment and disdain towards the diaspora and those who organized or proposed the fight?

Let us explore the data and the contexts surrounding remittances.

Historical context

It makes sense to go back in history to see where it all began to understand and appreciate the value of remittances for smaller economies. The money transfer industry started in the early days of international trading. During the era of colonialism, French and English soldiers would send money to their families. Lambrecht (2012) spoke about examples of servants in France and England that had part of their earnings from service remitted to close kin. "Servants allocated part of their earnings directly and indirectly to their family members, especially their parents." The same was valid for soldiers and their family members. We continue to see many sailors work on ships to support their families back home in modern times.

Haitians started to emigrate en masse circa the 1950s, and since then, they have always sent money back home. In Haiti, money transfers poured at a faster rate when many Haitians could leave the country to settle in the U.S., Dominican Republic, and Canada under the Duvalier Regime in the early sixties. Money transfer operators (MTO) competed to collect service fees on the remittances. Samuel L. Selden was one of the pioneers who established the Western Union (W.U.) in 1851. Money Gram (M.G.) came in 1940. According to the World Bank, Caribbean Airmail Inc. (CAM) accounts for 38% market share as an MTO operating in Haiti with an $11 service fee for a maximum of $500 transfer. The company opened its first locations in 1984 in New York and Miami. Confinity, now known as PayPal, came later in 1998. Lately, there have been all kinds of smartphone apps to transfer cash Venmo, Xoom, CashApp, Zelle, Ria, and many others. We will mainly focus on money sent abroad through CAM, W.U., and M.G.

Socioeconomic context

To understand the value of remittances in the lives of Haitians, it makes little sense to only look at the sheer monthly or yearly amount of cash that migrants send back home. The importance of the family's well-being forms a strong bond in maintaining the selflessness of senders. They send money to care for elders, parents, siblings, and other distant relatives. Roughly 40% of Haitian families receive money from abroad. The financial assistance comes from expatriates in foreign countries and from urban to rural areas. According to the migration data portal, which aims to provide comprehensive migration statistics and reliable information globally, there are multiple

• Should members of the diaspora focus instead on building a coalition that can support draft laws and financing election campaigns of individuals who can respond to our norms for a better Haiti.?

media to transfer funds to families and loved ones. Most data collected on remittances do not show money sent informally. The conventional data collection focuses on money flowing through banks and money transfer companies. The portal also talks about the value of temporary worker status, ONG Workers, residents who work for foreign countries. It also looks at diaspora investment, savings, and other financial transactions. In his opinion piece for the center for global development in 2013, Michael Clemens talks about three reasons why many countries with a large percentage of remittance in the GDP are not seeing any economic improvements. He argues that one, it is because of how official statistics record remittances; second, growth data are highly variable and therefore hard to quantify; and third, he says that constant migration can mask real GDP growth.

Another interesting indicator is the percentage of the GDP contribution of that amount. According to the Pew Research Center, remittances account for 31% of Nepal's GDP, Kyrgyzstan comes in second place with 30%, and Haiti is in third place with 29%. The same Research Center mentions a backward flow of $96,000,000 in remittances from Haiti to other countries in 2017. The 29% rate for Haiti may be a gross underestimation when factoring in money flowing into Haiti through other channels that are not accounted for.

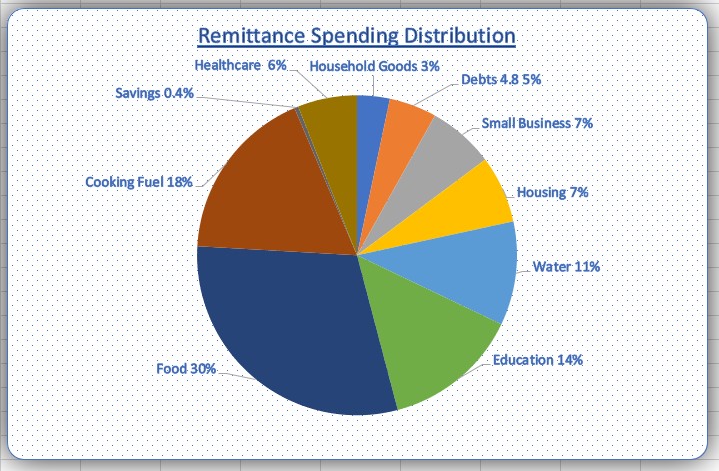

Haitians mainly use remittances to solve healthcare, rent, and food needs. An analysis of the data above points out the measly and insignificant percentage reserved for savings. The story in the graph above is that most Haitians are always indebted to those who can lend them cash until the remittance arrives. It shows that the amount received can barely help them survive. There is no capacity to start a small business.

Below is an approximate distribution of remittances in each sector of the economic life of the Haitian individual according to the humanitarian Practice Network. The numbers can be significantly different when comparing urban and rural areas.

We often hear a frequent argument in Haitian circles that the diaspora is guilty of leaving the country to fend for itself. Nevertheless, we all know that cannot be further from the truth. The diaspora has always shown altruism and is always ready to respond to the basic needs of their immediate family members and friends. When we look at what the expatriates have done to help Haiti regarding money transfers, food, large items purchase, real estate, tourism, donations, it is fair to say they have done their part. However, more can be done. A supplementary approach is needed.

The diaspora gives, but we do not receive anything in return. We have no right to vote. The various regimes that succeeded one another have used the diaspora as a cash cow. Members of the Haitian Diaspora are caught in a spiral to sacrifice more to prove patriotism. The current situation must change, and the tax levied against transfers must be more transparent. The Haitian Diaspora can demand greater transparency from the government about its use of the tax levied on the remittances or face the consequences of direct deposit to family members bypassing their tax collection system. The diaspora can control this boon and valuable resources by having autonomy and access to the information. How can we use our purchasing power to finance candidates with a more progressive, democratic, and transparent agenda?

Possible Solutions

A short halt on remittance - Can a sudden hiatus of a few weeks in money transfers to family members and friends from migrants be used as an effective tool in the fight for better democratic governance in Haiti? The answer may not be so simple. The dilemma revolves around the risks of interrupting the remittance for political gains being too significant and outweighing the benefits. While it certainly would impact a broad array of stakeholders, ranging from multinational corporations to big retailers, the country's most vulnerable citizens would suffer the most. Besides, it would be almost impossible to convince a large portion of the diaspora to participate. Fierce opposition would come primarily from those senders who do not want to participate in politics. Any halt in remittances would most likely further erode an already fragile economy. The people in Haiti would accuse the organizers of selfishness and cruelty. They would see a movement that leaves the unfortunate to their fate in Haiti while the diaspora thrives overseas.

Similar attempts in the past have all failed. President Donald Trump has tried remittance attrition to induce Mexico to pay for his border wall. It failed miserably. After the 1991 coup, the Organization of American States (OAS) and the U.S. imposed a trade embargo requesting the return of Aristide to power. The regime did not budge for three years until a military intervention brought Aristide back. The embargo did not necessarily affect the elites, but it hurt the population and led to extreme poverty and famine.

The recession of 2008 created havoc in Haiti. The council on hemispheric affairs found that Haiti, along with the greater Caribbean, "experienced a substantial decline in remittances following the 2008 global economic crisis. Fortunately, remittance flows to Haiti increased significantly in the aftermath of January 2010's earthquake"

The emergence of COVID-19 has, in part, devastated the Haitian economy. The world bank estimates that remittances will drop by 14% due to the pandemic compared to prior years. However, that turned out not to be the case. Gang activities are now causing terror for recipients to go collect their cash transfers.

Lessons learned; the needs of the Haitians are plentiful. After all, Haiti is a country where most of the population lives under $2 a day. The downside of lesser remittance transactions can cause more unemployment, and as a further consequence, mobs will take to the streets and start burning cars and businesses in an already fragile economy. We will also see people take to the sea on overcrowded boats, causing more embarrassment for all of us.

Awareness campaign to influence recipients to vote- According to Paarlberg from the Washington Post, he interviewed a D.C.-based campaign manager for the left party in El Salvador who told him, "If we get one Salvadoran in the U.S. to support us, that gives us five votes in El Salvador." It is extraordinary. The mechanisms to get votes in Haiti are not that different. The deceptive practice that politicians use to win elections is the same everywhere in the western world—then-candidate Vicente Fox gifted phone cards to get people in L.A. to call relatives to vote for him in the Mexican presidential election.

Ahmed (2016) concluded in his excellent research that remittances could reduce the perverse socioeconomic effects associated with such clientelist behavior by increasing the cost of buying electoral support. This can compel an incumbent to spend a larger share of his budget on providing welfare goods to the masses while reducing payments to a small group of voters. He also looks at another effect that people who are well off from stable remittances may fall for the illusion that an incumbent is doing well and helping the economy.

Organize targeted boycotts - The diaspora can be bolder and inspire a local boycott of specific products and services. It needs to encourage a more creative and selective approach to spending money. It needs to hurt the pocket of the elite few who contribute to the country's ailments. The recipients can be encouraged to buy only essential goods for a specific period. However, reaching a consensus depends on the population's ideal and cultural aspirations.

Finding alternative ways to send money to Haiti - Each year, a small percentage of the money sent to Haiti bypasses the conventional Western Union/CAM route. Some folks use friend travelers to push cash directly to family members. However, banks and transfer agents handle the bulk of transfers and withhold the tax that those in power misuse in secrecy. The high fees ultimately hurt those most in need in Haiti. The costs will continue to grow at the whims of politicians and the market in general. It, therefore, makes sense to say that we need new ways to deliver the funds for lesser fees.

Organized civil sector- Pirkkalainen (2015), in his book, looked at the value of the diaspora from 2 angles: Firstly, as an essential source of financial funding for areas in extreme poverty, and secondly, how the diaspora as a civil Society contributes to democracy. He argues that the diaspora can be active in civil society, working in organizations and supporting development initiatives. It can help provide services in the context of ongoing conflict, a fragile state, and extreme poverty and serve as counter-voices to conflicting parties by representing 'civility' and promoting non-violent means to achieve their goals.

Civil society is a network of individuals not considered in the public or private sectors. Civil society provides a counterbalance to the actions of the state. Any organization that is not an armed or belligerent group is part of Civil Society. As a loose band of individuals taking care of their family members in Haiti, the diaspora is not part of the civil sector until it flexes muscles in a collective activity. It needs to organize in a way that is not motivated by profits and still plays a commanding role in government decisions.

The Haitian diaspora needs the help of organizations that monitor and hold governments officials responsible for their policies and activities. It needs to engage in advocacy and propose alternative policies for good governance and a better environment for private enterprise. More importantly, it needs to support projects that offer services to the underserved. It should strive to alter societal norms and habits that are nefarious.

A banking system with microcredit initiatives - The diaspora should explore the introduction of a banking system that allows people to borrow low amounts of money to establish or develop small business initiatives. Other countries are looking into adopting a national digital currency. El Salvador has recently accepted bitcoin as legal tender. According to the IMF, other forms of digital money are increasingly being used for cross-border payments. Soon, remittances to Haiti will eventually be done using digital currencies, including cryptocurrencies and quantum technology.

Diaspora investment (Starting small enterprises) - Haiti's recipients of remittances, in large part, use the funds to consume materials imported from wealthy nations. In other words, the money sent ultimately comes back where it originated through purchasing goods from importers.

A good strategy is to look at how to reinvest excess remittances in business initiatives that provide sustainable growth.

For instance, $300 monthly from a family member who migrated to the U.S. may be pocket change for someone living in the U.S.; In Haiti, it can go a long way to feed an entire family in a month. In order to stop the reliance on remittance, a suitable alternative may be to invest in a small business endeavor in the informal economy. We must learn to put the skills of the recipients to good use. Imagine the plight of some young men if it were not for the moto-taxi ventures in Haiti. In Latin America, the streets are overflowing with merchants of the informal economy. There are food kiosks everywhere. Why can't the same be done in Haiti? We cannot continue to act as if the remittances are coming from a spigot; they will not continue to flow forever.

Recommended Solutions

Finance the campaign of a progressive candidate

In Haiti, the diaspora does not actively participate in the country's political affairs and civil society. There is still the fear of being killed by the supporters of the incumbent regime. It is a direct consequence of the terrorizing years of the Duvalier dictatorship. At the same time, the diaspora consumes news from the proliferating clandestine Haitian radio and web broadcasts; there is apathy towards organizing and donating to campaigns. The culture of donating is not in the Haitian frame of mind. However, they donate large sums to their churches.

Escribà-Folch et al. (2018), in their research paper on remittances and political protests, concluded that Popular uprisings are becoming a more frequent means of deposing autocracies, and they demonstrate that remittances in authoritarian environments fuel anti-regime movements. As a result, remittances may aid in the advancement of political change. The results of our individual-level studies support the theory that remittances boost protest by increasing the resources available to political opponents.

In the early 1990s, the Zapatista movement in Chiapas, Mexico, was partly due to the neoliberalism of NAFTA and the harsh exploitation and taxation policies that did not favor local development. The Chiapanecos organized under the EZLN organization to make their voices heard in the democratic process and have a say in the future of their lands. The Zapatistas protested the poverty faced by the indigenous Chiapanecos. They protested that they were treated as second-class citizens and their lands were at stake and could be lost. Although the movement did not last for long and was stopped early on, it spurred many good political reforms that improved the lives of the Chiapanecos and allowed them to gain seats in the national legislature.

The Haitian Diaspora needs leaders who can gain seats in the legislature to spur the same favorable political reforms. We need candidates with strong ideals and a clear vision to propel Haiti. These contenders will need all the apparatus and funding necessary for their fight. They must be leaders whose principal values include good faith and courage.

HAMREC must disclaim that the Johnson Amendment bans organizations 501(c)3 from supporting candidates to maintain their tax-exempt status.

Possible Outcomes

The possible outcome is an organized diaspora that will not blindly send money to Haiti while ignoring the value and power of what their transfers can do. We will end up with an electorate that can grow and encourage friends to go out and vote. By financing progressive campaigns in local elections, we remove the need to depend on a wealthy elite class that does not care about the plight of the less fortunate. Haitians abroad cannot vote, but they can convince their relatives back home to vote for a specific candidate. No communication barrier can impede such effort.

It is incumbent that we show the robustness and power of the flow of money transfers to Haiti. We do not intend to recommend that migrants stop sending money to Haiti. Besides, a few weeks of attrition can only warn leaders on the ground but not force a positive change on the political scene. However, we have other powerful weapons to force the hand of corrupt individuals at the helm of Haiti fate. We need bold measures to compel the nefarious actors who control Haiti's economy to debate and offer real and tangible change.

HAMREC's fight is about collecting and disseminating information on how to effectively control our resources for the dignity of all Haitians anywhere in the world.